GERD (or GORD) is an exceptionally common cause of consultation and can affect a great amount of people worldwide. As such, the treatment must be tailored to the patient severity of symptoms.

Lyfestile

General recommendations and lifestyle modification can be useful for most patients, such as weight loss in overweight and obese patients, avoiding meals within 2–3 hours of bedtime, avoidance of smoking as well as “trigger foods” which can relax the LES such as alcohol, chocolate, coffee, or alcohol. Elevating head of bed for nigh time is usually good recommendation especially when symptoms are night-time predominant. For long term maintenance of symptoms, these measures can be enough in sporadic or mild cases. I

Medication

On the majority of patients that consult for this complaint, PPIs are recommended over treatment with histamine-2-receptor antagonists (H2RA) both for symptoms and for healing erosive esophagitis when present. This is based on faster and more efficacious resolution with PPI when compared to H2RA described in metanalysis. The dose can be increased depending on the patient response, usually no more than x4 (i.e omeprazole, 40mg twice a day would generally be the maximum) and equally we should try to reduce the dose to the least possible that maintains adequate response.

There has been a well described safety of long-term proton pump inhibitor (PPI) t confirmed by the treatment of millions of patients over the past two decades. So much so, that the FDA approved for several of these medications to be sold over the counter. During early testing, gastric carcinoids were observed in animal models, but this complication has not been shown to occur in humans. There is also a theoretical concern that reducing gastric acid could interfere with the absorption of nutrients such as magnesium, calcium, iron, and protein. However, only magnesium absorption has been notably affected. Long-term PPI use has also been linked to a slight decrease in vitamin B12 levels, likely due to reduced absorption of protein-bound vitamin B12. As a result, it is recommended to periodically monitor vitamin B12 levels in patients on continuous PPI therapy for over five years.

Mild bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine has been observed in patients on chronic PPI therapy, but this generally remains clinically insignificant unless there is an underlying small bowel motility disorder or altered surgical anatomy. Observational studies have also associated PPI use with an increased risk of community-acquired pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infections, and hip fractures. Despite these potential concerns, current clinical evidence indicates that PPIs are generally safe for long-term use when clinically necessary. However, reducing the dose or discontinuing PPIs should be considered once symptoms are controlled, with the goal of maintaining patients on the lowest effective dose.

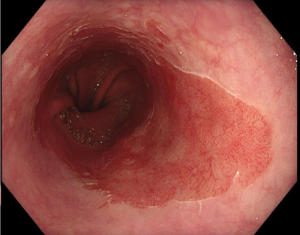

If a patient does not respond to PPI or has intolerance, this can be switched to a different one (they all have similar rate of effectiveness) or alternatively, switched to antiH2 medication. Reflux suppressant such as alginate (Gaviscon) can be added individually. Most patient will respond to PPI and lifestyle changes. It can be useful assessing any influence of polypharmacy, there has been medication such as anticholinergics, tricyclic antidepressants, calcium channel blockers, statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and nitrates that may associate with higher rates of GERD. Usually, the treatment is recommended for 8 weeks and then can be discontinued in most patients. If patient does not respond to treatment, GERD diagnosis should be questioned and more tests (EGD if not done before and PhMetry/manometry) should be done to clarify. It must be remembered that other conditions like cardiac chest pain or oesophageal dysmotility can present with similar symptoms. A small proportion of individuals will require long term medication to keep the symptoms at bay, but ideally, we can advise to take treatment only on demand when needed. Patients with Barret’s oesophagus or grade C-D oesophagitis should be treated lifelong to prevent adverse events or progression to dysplasia and adenocarcinoma.

In patients whose recurring symptoms are not controlled with medical treatment, or they wish not to be on long term medication, there usually is a potentially surgical option (laparoscopic anti reflux surgery, with or without hernia repairing depending on the case).

Antireflux therapy

Antireflux surgery has been performed since the 1950s, with the primary aim of reducing the lower esophageal luminal diameter to prevent the backflow of stomach and duodenal contents. The most commonly performed procedure is the Nissen fundoplication, which has shown a symptomatic improvement in 80-90% of patients, according to multiple studies. A review of six randomized controlled trials comparing open versus laparoscopic fundoplication found no significant difference in GERD recurrence rates between the two methods. However, the laparoscopic approach offered advantages such as reduced surgical morbidity and a shorter hospital stay. Despite the success of surgery, up to 62% of patients may require medication again within 10 years.

Common complications from fundoplication include dysphagia, chest pain, gas-bloat syndrome, increased flatulence post-surgery, and vagal nerve damage that can lead to gastroparesis and diarrhea. The prevalence of these issues ranges from 5% to 20%, with postoperative dysphagia occurring in up to 18% of patients, early dysphagia affecting about 20%, and late dysphagia observed in 6% at two years post-surgery. Additionally, antireflux surgery carries a small risk of operative mortality, between 0.5% and 1%, though this risk is lower with laparoscopic techniques and experienced surgeons. Since certain esophageal motility disorders can mimic GERD, it’s critical to conduct preoperative manometric testing to rule out underlying esophageal dysmotility that might worsen after fundoplication.

Other endoscopic procedures such EsophyX TIF ( peroral transmural fundoplication) Stretta (radiofrequency) ARMS or ARMA (Mucosal ablation with APC or mucosectomy) present variable results and will be discussed in the endoscopic chapter.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Katz, Philip O. MD, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 117(1):p 27-56, January 2022. | DOI: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001538

Lundell, L. R., et al. “Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification.” Gut 45.2 (1999): 172-180.

https://librepathology.org/wiki/Gastroesophageal_reflux_disease

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6839728/pdf/gutjnl-2018-318115.pdf

Zagari RM, Fuccio L, Wallander M, et al Gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms, oesophagitis and Barrett’s oesophagus in the general population: the Loiano–Monghidoro study Gut 2008;57:1354-1359.

Shaheen NJ, Richter JE. Barrett’s oesophagus. The Lancet. 2009;373(9666):850–861

Updates to the modern diagnosis of GERD: Lyon consensus 2.0. 2024 Jan 5;73(2):361-371. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2023-330616.

Rodríguez de Santiago et al. Antireflux mucosectomy (ARMS) and antireflux mucosal ablation (ARMA) for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2021 Nov 12;9(11):E1740-E1751. doi: 10.1055/a-1552-3239. PMID: 34790538; PMCID: PMC8589565.